POLLUTION AND PREVENTION

(Contains extracts

of material courtesy of IMO, AMSA, RMS &

A.N.T.A. publications,

Ranger Hope © 2017

Marine Pollution

The growth in the maritime transport of oil, size of new tankers,

increasing chemical carriage and a growing concern for the world’s environment left

the 1954 OILPOL Convention as inadequate. A new IMO Assembly prompted partly by

the

The resulting International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) was the most ambitious international treaty covering maritime pollution ever adopted. It deals not only with oil but with all forms of marine pollution from ships except the disposal of land-generated waste into the sea by dumping (which was covered by a previous London Sea Dumping Convention).

Australia is a party to the 1973/78 International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL 73/78 as amended) as well as the 1972 Convention on the prevention of Marine Pollution by dumping of Wastes and other Matter. Australian maritime pollution laws apply to vessels of all nations within 200 nautical miles offshore.

Australian Commonwealth

Legislation includes:

Navigation Act 2012

Protection of the Sea

(Harmful Anti-fouling Systems) Act 2006

The Environmental Protection (Sea Dumping)

Act 1981.

Great Barrier Reef

Marine Park Act 1975

The Protection of the Sea (Prevention of

Pollution from Ships) Act 1983.

Marine Orders are a form of delegated legislation

under Australia’s Commonwealth maritime laws that apply to Australian and

foreign vessels. Those that reference and regulate the Commonwealth Legislation

with regard to pollution control are:

MO91 Marine pollution prevention — oil

MO 93 Marine pollution prevention — noxious liquid substances

MO 94 Marine pollution prevention — packaged harmful

substances

MO 95 Marine pollution prevention — garbage

MO 96 Marine pollution prevention — sewage

MO 97 Marine pollution prevention — air pollution

MO 98 Marine pollution prevention — antifouling

Australian

State/Northern Territory legislation includes:

New South Wales- Marine Pollution Act

2012

South Australia- Protection of Marine

Waters (Prevention of Pollution from Ships) Act 1987

Western Australia- Pollution of Waters by

oil and Noxious Substances Act 1987

Tasmania- Pollution of Waters by

Oil and Noxious Substances Act 1987

Victoria- Pollution of Waters by

Oil and Noxious Substances Act 1986 Environment Protection Act 1970

Queensland- Transport Operations

(Marine Pollution) Act 1995

Northern Territory- Marine Pollution Act

1999

The Protection of the Sea (Prevention of

Pollution from Ships) Act 1983.

This Commonwealth Act is administered by the Australian Maritime Safety

Authority. The Act implements the International Convention for the Prevention

of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) in Australian Commonwealth waters.

Jurisdiction under this Act extends from 3 nautical miles (nm) out to the

Australia Exclusive Economic Zone (200 nm) and also applies within the 3nm

limits where a State/Territory government does not have complementary

legislation.

MARPOL

MARPOL includes regulations

aimed at preventing both accidental pollution, and pollution from routine

operations. Special Areas with strict controls on operational discharges are

included in MARPOL’s six technical Annexes:

Annex

I: Regulations for the prevention of pollution

by oil.

(oil

mixtures, distillates, gasoline, jet fuels, etc.)

Annex

II: Regulations for the control of pollution by

noxious liquid substances in bulk.

(mainly

chemicals including acids, alcohols, castor oil, hydrogen peroxide, pentane,

etc. Also citric juice, glycerine, milk, molasses, wine, etc.)

Annex

III: Regulations for the prevention of pollution by

harmful substances carried by sea in packaged form.

(includes

freight containers, portable tanks, road and rail tank wagons, etc.)

Annex

IV: Regulations for the prevention of pollution by

sewage from ships.

(wastes

from toilets, drainage from medical premises, drainage from spaces containing

live animals, etc.)

Annex

V: Regulations for the prevention of pollution

by garbage from ships.

(plastic

bags, synthetic ropes, food wastes, paper products, glass, metal, crockery,

packaging material, synthetic fishing nets, etc.)

Annex

VI: Regulations for the prevention of air

pollution from ships.

(smoke and fumes)

Annex I - Oil

Except where otherwise stated, these regulations apply to all tankers of

50 gross tons (about 30 metres in length) and above and other ships of 400

gross tons (about 40 metres) and above.

A complete ban on operational discharges of oil from ships except under

the following conditions:

For all ships,

1 The

rate at which oil may be discharged must not exceed 60 litres per mile

travelled by the ship;

2 The

oil content of any bilge water discharged must be below 100 parts per million;

3 Ship

must be more than 12 miles from nearest land; and

4 Ship must have in operation an approved oil discharge

monitoring and control system, oily water separating equipment or oil filtering

equipment.

For tankers,

1 No

discharge of any oil whatsoever must be made from the cargo spaces of a tanker

within 50 miles of the nearest land;

2 The total quantity of oil which a new tanker may discharge in

any ballast voyage must not exceed 1/30,000 of the total cargo carrying

capacity of the vessel. For existing tankers the limit is 1/15,000 of the cargo

capacity.

The definition of oil includes petroleum in any form including crude

oil, fuel oil, sludge, oil refuse and refined products (other than

petro-chemicals).

‘Nearest land’ is defined as the baseline used to establish the

territorial sea. However, the Convention makes a special case for the

The discharge of oil is completely forbidden in certain ‘special areas’

where the threat to the marine environment is especially great. These include

the

Parties to the Convention are obliged to provide adequate facilities for

the reception of residues and oily mixtures at oil loading terminals, repair

ports, etc.

Annex II - Noxious Liquid Substances

This section contains detailed requirements for discharge criteria and

measures for the control of pollution by noxious liquid substances carried in

bulk.

The substances are divided into four categories which are graded A to D

according to the hazard they present to marine resources, human health or

amenities.

Some 250 substances have been evaluated and included in a list which is

appended to the Convention.

As with Section I there are requirements for the discharge of residues

only into reception facilities unless various conditions, depending on the

category of the substance are complied with. In any case no discharge of

residues containing noxious substances is permitted within twelve miles of the

nearest land in a depth of water of less than 25 metres. Even stricter

restrictions apply in the

Every ship subject to the provisions of this section,

will be surveyed for compliance in a similar manner to oil tankers and other

ships under section I.

Operations involving substances to which Section II applies must be

recorded in a Cargo Record Book, which can be inspected by the authorities of

any Party to the Convention.

Annex III - Harmful Substances

In Packaged Form

This section applies to all ships carrying harmful substances in

packaged forms, or in freight containers, portable tanks or road and rail tank

wagons. It requires the issuing of detailed requirements on packaging, marking,

labelling, documentation, stowage, quantity limitations, exceptions and notifications,

for preventing or minimising pollution by harmful substances. To help implement

this requirement the International Maritime Dangerous Goods Code is being

revised to cover pollution aspects.

Annex IV - Sewage

Ships are not permitted to discharge sewage within four miles of the

nearest land unless they have in operation an approved treatment plant. Between

three and twelve miles from land sewage must be comminuted

and disinfected before discharge.

Under Annex IV of MARPOL, it is proposed that the discharge of sewage

from ships should be controlled in all coastal areas in a manner similar to

that of garbage.

• New

vessels of 400 gross registered tonnes and over.

• New

vessels certified to carry more than 15 persons.

• Existing

vessels of 400 gross registered tonnes and over (to be fitted within 10 years).

• Existing vessels

certified to carry more than 15 persons (to be fitted within 10 years).

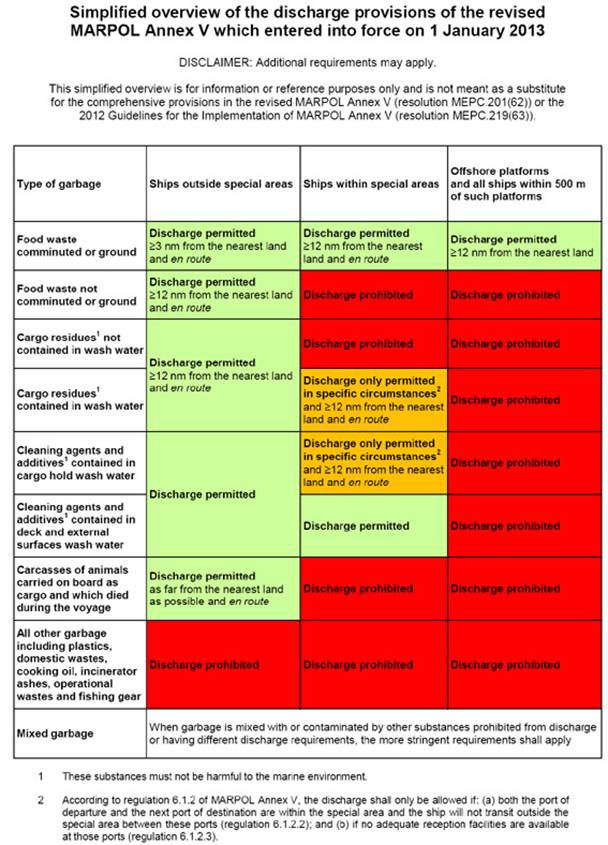

Annex V - Garbage

As far as garbage is concerned, specific minimum distances have been set

for the disposal of the principal types of garbage. Perhaps most important

feature of this section is the complete prohibition placed on the disposal of

plastics, including synthetic ropes and fishing nets into the sea.

Every ship of 100 gross tonnage (instead of 400

GT required by the superseded MARPOL Annex V) and above, and every ship which

is certified to carry 15 or more persons, shall carry a garbage

management plan (based on IMO Guidelines and in working language of the

crew) containing procedures on:

- garbage minimization

- garbage collection

- garbage storage

- garbage processing

- garbage disposal

- equipment used onboard for handling of

garbage

- the designation of the person or

persons in charge for implementing the Garbage Management Plan

National Plan To Combat Marine Pollution

This was set up after the grounding of the Oceanic Grandeur in

Stockpiles of dispersant materials and equipment are set up at 9 ports

around

Dumping At Sea

Under the Australian Environmental Protection (Sea Dumping) Act 1981,

licences are needed by all involved in the operation of dumping at sea. This

law relates to dumping of sand, gravel, factory waste and other materials.

The Effects Of

Oil On Wildlife

We have all seen pictures and videos of wildlife covered in black,

sticky oil after an oil spill. These pictures are usually of oiled birds. Many

people are not aware that it is not just birds that get oiled during a spill.

Other marine life such as marine mammals can also suffer from the effects of an

oil spill. Even small spills can severely affect marine wildlife.

Not all oils are the same. There are many different types of oil and

this means that each oil spill is different depending on the type of oil spilt.

Each oil spill will have a different impact on wildlife and the surrounding

environment depending on:

• the type of oil spilled,

• the location of the spill,

• the species of wildlife in the area,

• the timing of breeding cycles and

seasonal migrations,

• and even the weather at sea during

the oil spill.

Oil affects wildlife by coating their bodies with a thick layer. Many

oils also become stickier over time (this is called weathering) and so adheres

to wildlife even more. Since most oil floats on the surface of the water it can

effect many marine animals and sea birds.

Unfortunately, birds and marine mammals will not necessarily avoid an oil

spill. Some marine mammals, such as seals and dolphins, have been seen swimming

and feeding in or near an oil spill. Some fish are attracted to oil because it

looks like floating food. This endangers sea birds, which are attracted to

schools of fish and may dive through oil slicks to get to the fish.

Oil that sticks to fur or feathers, usually crude and bunker fuels, can

cause many problems. Some of these problems are:

• hypothermia in birds by reducing or

destroying the insulation and waterproofing properties of their feathers;

• hypothermia in fur seal pups by

reducing or destroying the insulation of their woolly fur (called lanugo).

Adult fur seals have blubber and would not suffer from hypothermia if oiled.

Dolphins and whales do not have fur, so oil will not easily stick to them;

• birds become easy prey, as their

feathers being matted by oil make them less able to fly away;

• marine mammals such as fur seals

become easy prey if oil sticks their flippers to their bodies, making it hard

for them to escape predators;

• birds sink or drown because oiled

feathers weigh more and their sticky feathers cannot trap enough air between

them to keep them buoyant;

• fur seal pups drown if oil sticks

their flippers to their bodies;

• birds

lose body weight as their metabolism tries to combat low body temperature;

• marine mammals lose body weight when

they can not feed due to contamination of their environment by oil;

• birds become dehydrated and can

starve as they give up or reduce drinking, diving and swimming to look for food;

• inflammation or infection in dugongs

and difficulty eating due to oil sticking to the sensory hairs around their

mouths;

• disguise of scent that seal pups and mothers rely on to

identify each other, leading to rejection, abandonment and starvation of seal

pups; and

• damage to the insides of animals and

birds bodies, for example by causing ulcers or bleeding in their stomachs if

they ingest the oil by accident.

Oil does not have to be sticky to endanger wildlife. Both sticky oils

such as crude oil and bunker fuels, and non-sticky

oils such as refined petroleum products can affect different wildlife. Oils

such as refined petroleum products do not last as long in the marine

environment as crude or bunker fuel. They are not likely to stick to a bird or

animal, but they are much more poisonous than crude oil or bunker fuel. While

some of the following effects on sea birds, marine mammals and turtles can be

caused by crude oil or bunker fuel, they are more commonly caused by refined

oil products.

Oil in the environment or oil that is ingested can cause:

• poisoning of wildlife higher up the food chain if they eat

large amounts of other organisms that have taken oil into their tissues;

• interference with breeding by making the animal too ill to

breed, interfering with breeding behaviour such as a bird sitting on their

eggs, or by reducing the number of eggs a bird will lay;

• damage to the airways and lungs of

marine mammals and turtles, congestion, pneumonia, emphysema and even death by

breathing in droplets of oil, or oil fumes or gas;

• damage to a marine mammal’s or

turtle’s eyes, which can cause ulcers, conjunctivitis and blindness, making it

difficult for them to find food, and sometimes causing starvation;

• irritation or ulceration of skin, mouth

or nasal cavities;

• damage to and suppression of a

marine mammal’s immune system, sometimes causing secondary bacterial or fungal

infections;

• damage to red blood cells;

• organ damage and failure such as a

bird or marine mammal’s liver;

• damage to a bird’s adrenal tissue

which interferes with a bird’s ability to maintain blood pressure, and

concentration of fluid in its body;

• decrease

in the thickness of egg shells;

• stress;

• damage to fish eggs, larvae and

young fish;

• contamination of beaches where

turtles breed causing contamination of eggs, adult turtles or newly hatched

turtles;

• damage to estuaries, coral reefs,

seagrass and mangrove habitats which are the breeding areas of many fish and

crustaceans, interfering with their breeding;

• tainting of fish, crustaceans, molluscs and algae;

• interference with a baleen whale's feeding system by tar-like

oil, as this type of whale feeds by skimming the surface and filtering out the

water; and

• poisoning of young through the mother, as a dolphin calf can

absorb oil through it’s mothers milk.

Animals covered in oil at the beginning of a spill may be affected

differently from animals encountering the oil later. For

example, early on, the oil maybe more poisonous, so the wildlife affected early

will take in more of the poison. The weather conditions can reduce or

increase the potential for oil to cause damage to the environment and wildlife.

For example, warm seas and high winds will encourage lighter oils to form

gases, and will reduce the amount of oil that stays in the water to affect

marine life.

The impact of an oil spill on wildlife is also affected by where spilled

oil reaches. For example, fur seal pups are affected more than adults by oil

spills because pups swim in tidal pools and along rocky coasts, whereas the

adults swim in open water where it is less likely for oil to linger. Dugongs

feed on seagrass along the coast and therefore be more

affected by oil spills.

Different resources will be needed to combat an oil spill, depending on

the number and type of wildlife that is affected. Quick and humane care of

wildlife affected by oil spills is required by law. The National Oiled Wildlife

Response guidelines have been developed at both the Commonwealth and

State/Territory level under

Pollution Prevention From

“Small” Vessels

• Observe

anti-spill and fire precautions when re-fuelling.

• Don’t

discharge oily bilges within 12 nautical miles from coast. Observe the above

guidelines when discharging outside 12 miles. Oily bilges must be discharged into

a mobile or a shore based pump-out facility. Observe the above “large vessel”

guidelines when discharging at sea. Bilge water can easily be cleaned by

installing an oil absorbent pad or a oily water

separator near the bilge pump. Bilge sponges are available from most chandlers.

• Don’t

discharge plastics anywhere

• Observe

the discharge of garbage, toilet waste and noise pollution regulations stated

above.

• If

your vessel is within 12 nautical miles from land you must retain all garbage

on board for disposal ashore. However, if you have a grinder or similar garbage

processor on board your vessel, you may discharge processed non-plastic garbage

at a distance greater than 3 nautical miles from land. No form of garbage can be dumped within 3 nautical miles from land for reasons of

visual and beach pollution etc.

• Decant

cooking oils and fats into suitable container and take home for disposal. Wipe

plates clean with a paper towel before washing up.

• Use

minimal amounts of washing detergent.

• Engine

oil must only be discharged into an oil reception barge or a shore facility.

• If

a vessel is not fitted with a separate oily waste tank, oily bilge water should

be pumped into a container on deck for disposal when ashore.

• Fishing

vessels must make ever effort to retrieve all lost or damaged fishing gear.

Lost fishing gear should be reported to the Federal Sea Safety Centre in

• No

discharge of any type is permitted in the specially protected area of the

• Waterways officers have the power to order any vessel

creating excessive noise from its engines to leave the water. Power boats must

be fitted with an efficient silencer and operated with regard for other

waterway users and nearby residents. Moored sailing vessels too must control

noise pollution by preventing loose rigging slapping against the mast. Sound

carries long distances over water.

• When using launching

ramps, particularly in the early morning, be conscious

of the annoyance for nearby residents created by conversation and motors.

• You

are required to report any polluting spill from your own vessel, and, requested

to report sighting of any other.

• In

most areas, the tidal flushing characteristic, of estuarine waterways protect

water quality from toilet waste. However, in non-tidal waters, all commercial

vessels of 6 metres or longer must be equipped with holding tanks and ancillary

pollution control equipment. In addition, all vessels (commercial or

non-commercial) operating in certain non-tidal areas must be fitted with a

holding tank and ancillary pollution control equipment, if:

• there is a

toilet on board,

• the vessel is 6 metres or longer and is equipped with

sleeping accommodation.

On the non-tidal Murray-Darling system in NSW there are pump ashore

stations at Wentworth, Buronga and Moama. At these stations, vessels can pump

out their holding tanks and portable toilets in to the town sewerage system.

At the non-tidal

NSW Plan

1 Legislation

to require vessels suspected of causing pollution to deposit a bond sufficient

to cover clean-up costs and possible penalties before being allowed to sail. It

affects mainly large seagoing vessels.

2 Recent

changes to the Management of Waters and Waterside Lands Regulations NSW make it

an offence for vessels to discharge toilet wastes into the waters of

In

summary, from July 1992, new boats with toilets will need to be fitted with a

holding tank, storage toilet or on-board treatment facilities: Older boats may

retain their pump through toilets but may not discharge waste in

Various

pump-out facilities are being, provided including one at Wharves 20-21 Pyrmont.

3 Prohibition of discharge of sewage and garbage from recreational

and commercial vessels into New

No discharge of waste (including kitchen and toilet waste) is permitted

in harbours and inland waters. “Grey water”, that is, wastewater from showers,

galleys and laundries, is usually not included in the Acts. Vessels are

expected to bring the garbage ashore in garbage bags and may be required to fit

holding tanks for toilet waste or carry portable toilets that are to be emptied

into pump out facilities. Vessels may also fit an on-board waste treatment

system approved by an Authority. Oily bilges must be discharged into a mobile

or a shore based pump-out facility.

In addition to the public pump-out facilities in some harbours and

waterways, certain marina and yacht clubs are required to install facilities

for their own customers.

Many State authorities are empowered to impose “on the spot” fines for

breaches of their pollution legislation. Penalties for non-compliance are high:

as much as $260,000 for an individual and over $1 million for the company that

owns the law -breaking vessel.

The operator of a busy party boat would need to consider a number of

issues in developing and implementing an effective Garbage management plan.

These might include:

• Signage

• Bins

• Disposal

facility ashore

• Recycling

plan

• Monitoring and review of the management plan

Vessel Sewage Management

• No

discharge of untreated sewage in harbours and inland waterways.

• No

discharge of treated or untreated sewage in:

• waterways in

which aquaculture, including oyster growing, occurs.

• waterways which

are used for drinking water supplies

• in or near a

bathing area, mooring area, marina and anchorage area.

• Class

4E commercial vessels over 6 metres (e.g. houseboats) to install holding tanks

for discharge into sewage pump-out facilities.

• Class

1 commercial vessels (passenger carrying vessels) to install holding tanks for

discharge into sewage pump-out facilities.

• Recreational vessel operators to suitably manage sewage from

their vessels, depending on the conditions applying to waterways in which they

operate, the length of the journey and the type of activity being undertaken.

The master of a vessel in NSW waters, should

develop a sewerage management plan, including:

• Maintenance

• Pump

out schedule and record book

• Monitoring and reviewing of plan

Refuelling

• Take

portable tanks out of the vessel for filling.

(Do

not carry spare fuel in plastic containers. They can rupture without being

noticed.)

• Hoist

flag B for refuelling internal tanks.

• Keep

watch.

• No

smoking.

• No

fires and no motors running.

• Disconnect

the battery.

• Turn

off gas.

• Have

a suitable fire extinguisher available near the filling station.

• Check

for leaks.

• Block

off deck scuppers and freeing ports to contain any spill on deck.

• Secure

vessel properly alongside.

• Provide

earth connection to or discharge static electricity from the fuel hose.

• Keep

the fuel nozzle in contact with the filler pipe to prevent static electricity

build up.

• Make

sure the fuel goes into the correct tank.

• Constantly

monitor the tank being filled.

• Consider

stability when filling side tanks.

• Fill

slowly towards the end.

• On

disconnection of fuel line, catch any spillage in a container.

• Clean

up any spill immediately.

• Keep

the vessel well ventilated, and close up enclosed spaces.

• Ventilate for some time before starting engine.

In Case Of An Oil Spill

• Cease operation

• Ease pressure on overflowing tank.

• Sound emergency alarm

• Ban smoking anywhere on board

• Take all fire precautions

• Control spill

• Inform authorities

• Clean up on deck

Pollution may not be an

offence when it is

necessary to jettison or discharge pollutants to save a vessel and her crew

from grave danger.

Fuel Expansion In Hot Weather

Fuel expands in volume about 0.5% per 1°C rise in temperature.

Therefore, with a 10° rise in air temperature - a common daily fluctuation in

Oil And Coolant Drainage System

The illustration shows a central waste pump set up to extract dirty lube

oil, engine coolant and bilge liquid. Once collected into a container, the

liquids are disposed off ashore in an environmentally safe manner.

Oil

And Coolant Drainage System

(Volvo Penta)

Some engines can be drained with a hand-operated drainage pump.

Installing an electric pump is another option. The pump can be run in either

direction by changing the polarity. To prevent engine being accidentally

drained, connect the pump hose only when changing oil.

Oil

Drainage Pump

Planned Maintenance

The Master is responsible for the

seaworthiness of the vessel and must ensure that all national and international

requirements regarding safety and pollution prevention are being complied with.

Effective planning is required to ensure that the vessel, its machinery systems

and its services are functioning correctly and being properly maintained,

including dry-docking to maintain hull smoothness.

Planned maintenance is primarily

concerned with reducing breakdowns and the associated costs. Planned

maintenance is of two kinds:

Preventative

maintenance is aimed at preventing failures or detecting failures at an early

stage.

Corrective

maintenance is aimed at repairing failures that were expected, but were not

prevented because they were not critical for safety or economy.

Slipping and repair work to vessels ashore creates special risks of

pollution. Some simple methods of minimising problems are given in each of the

following typical repair operations:

|

Pollution Risk |

Solution |

|

Dust from

sandblasting, (minimised by) |

screens |

|

Paints and

solvents leaching back to watercourse |

sediment

traps |

|

Noise from

sanding hull |

screens |

|

Oily bilge

water (beneath docking plugs) |

catch-alls

under plugs |

Pollution From Anti-Fouling

Antifouling prevents marine growth on the hull, but it is also generally

damaging to the environment. Law is continually restricting the permitted

leakage of the active ingredients in paints.

Regulations for small vessels are stricter than for large vessels. The

reason given is that small vessel harbours are mostly located in shallow waters

or fresh waters, which are also the spawning ground for fish. Furthermore,

small vessels spend most of their time tied up in harbours. This adds to the

impact on the environment of these waters.

A little thoughtfulness before using an anti-fouling paint goes a long

way. For example, trailer boats, which spend most of their life out of water,

do not need to use them. All they need is a Teflon treatment, combined with

sponge cleaning a few times during the season.

Fuel Saving

Alternative To Antifouling

Lanolin is made from wool grease - the

water-repellent that protects sheep from harsh effects of weather. It is now,

commercially available in cans. When coated on hulls of vessels, it makes them

slippery. It is claimed to not only make boats go faster, but also eliminate the

need for anti-fouling.

Non-TBT Antifoulings (some

still under trial)

1. Foulant-Release Coatings: These so called ‘non-stick

coatings’ are silicon elastomers. Their service life is claimed to be similar

to that of TBT, but are costly.

2. Ceramic-Epoxy

Coatings: Suitable for fibreglass as well as metal hulls.

3. Epoxy-Copper

Flake Paints: A bonded-copper system, which claims to protect boats for up to

10 years but cannot be used on aluminium hulls.

4. Electric

Current Systems: They produce hyperchlorite from

seawater on the surface of the hull, which is said to sterilise the surface for

up to 4 years. Another similar system uses alternating current and a conductive

hull coating.

5. Biological Compounds: About 50 natural substances are being

trialled.

Sensitive Enviroments

- Great Barrier Reef

Under MARPOL, no discharge of any type is permitted in the area of

Area

of no discharge (2005)

Fishing

Vessels

Fishing vessels must make every effort to retrieve all lost or damaged

fishing gear. Lost fishing gear should be reported to the Australian Rescue

Co-ordination Centre (RCC) in

Introduced

Marine Pests Program

What

Is The Introduced Marine Pests Program

The Introduced Marine Pests Program is a key platform in the Federal

Government’s response to introduction of exotic marine pests such as Northern

Pacific seastars and Japanese kelp in the Australian

marine environment. The Program’s overall goal is to support actions that will

ultimately lead to the control and local eradication of introduced marine pest

species.

The Program provides advice and funds to help combat marine pest

outbreaks. In doing so, it complements the barrier controls set in place by the

Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service under the Australian Ballast Water

Management Strategy.

Why Do We Need An Introduced

Marine Pests Program?

To date,

The Introduced Marine Pests Program is working to overcome these

problems by building the elements of a national incursion response capability.

The establishment of a comprehensive introduced marine pest incursion

management system is one of the key initial actions identified in

Funding

Priorities Of The Introduced Marine Pests Program?

Funding is being directed to help government, industry and community

stakeholders determine the major impacts of exotic marine species and

activities that allow pests to take hold. The Program will also help develop

the best ways to counter these threats.

Funding priorities for the Program are:

1. improve understanding of the impacts of pest species;

2. implement technology and techniques that contribute to

control and eradication;

3. respond to selected incidents of new pest incursions;

4. increase community awareness of and

participation in introduced marine pest issues.

Don’t Confuse Algal Blooms With Oil

Sometimes it is easy to confuse naturally accruing algal blooms with

oil. Floating Sea Scum (Trichodesmium) is common in

early summer. It is algal plant life in tones of red. yellow

or brown. Algae decaying along the shoreline can also turn greenish or release

a purple dye. It may appear in large beach slicks, often accompanied by putrid

fishy, chlorine, iodine or oil smell. But, unlike oil, it will wash off in

water.

Coral Spawns: Corals in places such as the

Stranding Or Grounding

Stranding is the accidental grounding

of a vessel on a beach, reef or shoreline while grounding is the accidental

contact with the seabed other than the shoreline.

Actions To Take (accidental stranding or

grounding):

• sound

the alarm to muster the crew/passengers (7 short, 1 long)

• stop engines and auxiliaries if

grounding is severe

• account for all

personnel and check for injuries

• sound all bilges and tanks to ascertain

whether the ship has been holed

• using a lead line sound all around the

vessel to ascertain the extent of the grounding. This

will determine whether the vessel’s stern is still afloat or grounded for her

whole length, and indicate where the deepest water lies.

• take bearings and plot your position -

then attempt to determine the type of grounding from the chart

• determine the tide and tidal stream

• check weather forecasts for the area

• check for hull damage (if damage has

occurred it may be best to stay grounded, while repairs are carried out).

If the hull is found to be intact and

the stern of the vessel is floating, the first attempt at refloating is to go

astern on the engines. However, this should not be too prolonged because the

wash may tend to build up sand or mud against the vessel’s side making matters

worse.

If this fails it is probably because

the force of the impact has forced out the water between the vessel’s hull and

the seabed creating a vacuum seal. The most effective method to break the

vacuum seal is to lightening the vessel aft so that the stern lifts allowing

water to find its way under the forward part of the vessel’s hull. This can be

done by pumping out aft ballast tanks, or jettisoning weights.

If the ship is not in immediate danger

and the tide is rising it may be prudent to wait for a rise in the tide before

attempting to refloat again.

If grounded on a reef at night in an uncertain

location, it may be prudent to stay grounded and add ballast to prevent further

damage to the hull due to movement of the vessel on the reef.

If the vessel has grounded for her

entire length the situation is more serious. Two anchors will have to be

carried out from the stern and laid out in tandem.

Another method is to lay two anchors

out from the stern - one from each quarter. By hauling on each anchor in turn

it may be possible to yaw (wag the vessel’s tail) thus helping to break the

vessel free. Engines may be used ahead with the rudder hard over first one way

and then the other to assist the operation.

If the vessel has grounded on a rocky

coast then the danger of hull damage is much greater. However, the vessel is

likely to have only a small portion of her hull in contact with the seabed. A

vacuum seal is not a possibility in this case and refloating may be very

difficult or impossible. If contact is made with the seabed at one point only,

pumping ballast, shifting (or jettisoning) weights in an attempt to alter trim

or to list the vessel may help.

If attempts to

refloat the vessel by the above means fail, then assistance will have to

be obtained. Another vessel or a tug may be required to tow the vessel off. If

a tug is used, make it fast alongside if possible as the scouring effect of the

tug’s propeller wash will assist to free the vessel. Display the appropriate

signal for a ‘vessel aground’.

Once clear of the obstruction it will

be necessary to again check the vessel for any damage or ingress of water. Also

check propulsion, steerage systems and engine cooling systems.

Note events in the vessel’s official

logbook or record book and make

a report to the appropriate Marine Authority, even if there is no damage

NSW Marine Pollution Act 2012

Part 6 Prevention of pollution

by sewage

Division 1 Offences

relating to discharge of sewage

53 Discharge of sewage

into State waters from ship prohibited

(Reg 11 of Annex IV of

MARPOL)

(1) The master and the owner of a large

ship are each guilty of an offence if any sewage is discharged from the ship

into State waters.

Maximum penalty:

(a) in the

case of an individual—$55,000, or

(b) in the

case of a corporation—$275,000.

(2) In proceedings for an offence against

this section in relation to a ship:

(a) it is

sufficient for the prosecution to allege and prove that sewage was discharged

from the ship into State waters, but

(b) it is a defence if it is proved that, by virtue of Division 2, this

section does not apply in relation to the discharge.

54 Causing discharge of

sewage into State waters from ship prohibited

(Reg 11 of Annex IV of

MARPOL)

(1) A crew member of a large ship is

guilty of an offence if the crew member’s act causes any sewage to be

discharged from the ship into State waters.

Maximum penalty: $55,000.

(2) A person involved in the operation or

maintenance of a large ship is guilty of an offence if the person’s act causes

any sewage to be discharged from the ship into State waters.

Maximum penalty:

(a) in the

case of an individual—$55,000, or

(b) in the

case of a corporation—$275,000.

(3) In proceedings for an offence against

this section, it is sufficient for the prosecution to allege and prove that:

(a) a

discharge of sewage occurred from a ship into State waters, and

(b) the crew

member or person involved in the operation or maintenance of the ship committed

an act that caused the discharge.

55 Offence of being

responsible for discharge of sewage into State waters from a ship

(Reg 11 of Annex IV of

MARPOL)

A person responsible for the discharge of any

sewage from a large ship into State waters is guilty of an offence.

Maximum penalty:

(a) in the

case of an individual—$220,000, or

(b) in the

case of a corporation—$1,100,000.

Division 2 Defences

56 Defence for discharge

caused by damage to ship or equipment

(Reg 3.1.2 of Annex IV

of MARPOL)

Division 1 does not apply to the discharge of

sewage from a large ship if:

(a) the

sewage escaped from the ship in consequence of unavoidable damage to the ship

or its equipment, and

(b) all

reasonable precautions were taken before and after the occurrence of the damage

for the purpose of preventing or minimising the

escape of the sewage.

57 Defence for discharge

to secure safety or save life

(Reg 3.1.1 of Annex IV

of MARPOL)

Division 1 does not apply to the discharge of

sewage from a large ship for the purpose of securing the safety of a ship or

saving life at sea.

58 Defence for discharge

of comminuted and disinfected sewage not less than 3 nautical miles from the

nearest land

(Reg 11.1.1 of Annex

IV of MARPOL)

Division 1 does not apply to the discharge of

sewage from a large ship if:

(a) the sewage has been comminuted

and disinfected using a system approved in accordance with the regulations, or

orders made pursuant to the regulations, giving effect to Regulation 9.1.2 of

Annex IV of MARPOL, and

(b) the

discharge occurs when the ship is at a distance of not less than 3 nautical

miles from the nearest land (within the meaning of Annex IV of MARPOL), and

(c) if the

sewage has been stored in holding tanks or originates from spaces containing

living animals—the sewage is not discharged instantaneously but is discharged

at a rate prescribed by the regulations when the ship is proceeding en route at

a speed of not less than 4 knots.

59 Defence of discharge

of treated sewage

(Reg 11.1.2 of Annex

IV of MARPOL)

(1) Division 1 does not apply to the

discharge of sewage from a large ship engaged in overseas voyages if both of

the following apply:

(a) the

sewage has been treated in a sewage treatment plant on the ship, being a plant:

(i) that an inspector has certified meets the requirements of

the regulations giving effect to Regulation 9.1.1 of Annex IV of MARPOL, and

(ii) the test results of which are

laid down in the ship’s sewage certificate within the meaning of Division 12C

of Part IV of the Navigation Act 1912 of the Commonwealth,

(b) the

effluent does not produce visible floating solids in State waters and does not cause

discolouration of State waters or other surrounding

waters.

(2) However, the defence

created by subsection (1) does not apply to a discharge into a zone prescribed

by the regulations for the purposes of this section.

The NSW Maritime Pollution Act allows for right to enter and inspect commercial vessels regarding possible infringements of the regulations if they suspect that the vessel could cause an incident.

Dangerous

Goods

The International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code is published by

the International Maritime Organisations (IMO). It comes in 4 volumes to which

a country may add a supplement to cover any variations of regulations. The IMDG

Code is popularly known as the Blue Book. It gives detailed instruction on the

safe packing and stowage of dangerous goods for carriage on ships which are not

specifically designed or converted as a whole for that purpose.

The carriage of dangerous goods by sea is prohibited except in

accordance with the provision of the Blue Book. They do not, however, apply to

ship’s stores and equipment.

Classification

Dangerous goods are divided in the IMDG Code into the following classes:

Class 1: Explosives

Class 2: Gases:

compressed, liquefied or dissolved under pressure.

Class 3: Inflammable

(or flammable) liquids.

Class 4.1: Inflammable

solids

Class 4.2: Inflammable

solids, or substances; liable to spontaneous combustion.

Class 4.3: Inflammable

solids, or substances, which in contact with water emit inflammable gases.

Class 5.1: Oxidising

substances.

Class 5.2: Organic

peroxides.

Class 6.1: Poisonous

(toxic) substances.

Class 6.2: Infectious

substances.

Class 7: Radioactive

substances.

Class 8: Corrosives

Class 9: Miscellaneous dangerous substances, that is

any other substance which experience has shown, or may show, to be of such a

dangerous character that the provision of this Chapter should apply to it.

NOTE: “Inflammable” has the same meaning as

“flammable”.

IMDG Labelling Of Dangerous Goods

All

Lettering Black

International

Maritime Dangerous Goods Code

United

Nations Labelling

Numbers

1 - 8 indicate classification

The Law

Relating To Dangerous Goods In NSW.

The following laws are contained in the NSW Navigation Act 1901:

Carriage Of

Dangerous Goods

1 No person shall be entitled to carry in any ship or to require

the master or owner thereof to carry therein any aquafortis,

oil of vitriol, gunpowder, nitroglycerine, or any

other goods of a dangerous nature.

2 If any person carries or sends by any ship any goods of a

dangerous nature without distinctly marking their nature on the outside of the

package containing the same and giving notice in writing to the master or owner

at or before the time of carrying or sending the same to be shipped, he shall

for every such offence incur a penalty not exceeding two hundred dollars.

3 The master or owner of any ship may refuse to take on board

any parcel or package that he suspects to contain goods of a dangerous nature,

and may, to satisfy himself of the contents thereof, require such parcel or

package to be opened in his presence:

Ships

Not To Be Loaded So As To Endanger Their Safety Etc.

1 If the carriage on any ship or vessel of any cargo, live

stock, provisions, water or stores would endanger her safety, or interfere with

the comfort of her passengers, no master or owner of such ship or vessel shall

allow such cargo, live stock, provisions, water, or stores to be carried or

stowed onboard.

2 The Board may require the master or owner of any steamship

entitled by her certificate to carry a certain quantity of live stock to

provide such fittings for such stock as it deems requisite.

3 The Board shall be the proper authority to determine whether

in any case the safety of the ship is endangered or the comfort of the

passengers interfered with.

4 Any master or owner who after notification from the Board that

his ship or vessel is loaded in any manner as hereinbefore prohibited proceeds

to sea or gets under weigh shall be liable to a penalty not exceeding two hundred

dollars.

Stowage Of

Cargo, Grain Etc.

1 No cargo of which more than one-third consists of wheat,

maize, oats, barley, or any other kind of grain (hereinafter referred to as

grain cargo) shall be loaded on board any ship in any port or place in New South

Wales unless such grain cargo is contained in bags, sacks, or barrels, or

secured from shifting by boards, bulkheads or otherwise.

2 Any managing owner, or master, or the agent of such owner, who

being charged with the loading of such ship or the sending her to sea,

knowingly allows any grain cargo or part of a grain cargo to be shipped therein

for carriage contrary to the provisions of this section shall for every such

offence be liable to a penalty not exceeding two hundred dollars.

What This Means

You must not carry dangerous goods unless it is safe to do so. They must

be properly packed and labelled. The containers must be in good condition. The

Blue Book should be consulted regarding handling, stowage and separation of

cargoes on board.

The skipper must produce a Notice of Intention to Ship Dangerous Goods,

duly endorsed by the Maritime Services Board.

The master can refuse or jettison any cargo which they suspect contain

goods of a dangerous nature. All port regulations and fire, pollution and safety

precautions must be observed.

While unloading a mixed cargo, an operator may take the following

precautions to lessen the risks of a pollution incident.

Safety Alongside the Wharf:

• Vessel properly secured

• Cargo nets and Safety nets in place

• Unwanted personnel kept clear

• Crew to wear safety gear

• Cargo watch established

• The

cargo must therefore be labelled, stowed and transported as per the IMDG

regulations

Part 9 Reporting of

pollution incidents

Division 1 Meaning of

“reportable incident”

86 Meaning of “reportable incident”

In this Part:

reportable incident, in relation

to a ship, means any of the following:

(a) a discharge or probable

discharge into State waters from the ship of oil other than a discharge of the

kind or in the circumstances specified in sections 22–25,

(b) a discharge or probable

discharge into State waters from the ship of a noxious liquid substance (other

than a substance referred to in Regulation 6.1.4 of Annex II of MARPOL) other

than of the kind or in the circumstances specified in sections 35–41,

(c) a jettisoning or probable jettisoning from the ship into

State waters of a harmful substance in packaged form including a substance in a

freight container, portable tank, road and rail vehicle or shipborne

barge,

(d) in relation to a ship of 15 metres in length or above that is carrying oil or a noxious

liquid substance:

(i) any damage, failure or

breakdown of the ship that affects the safety of the ship, including but not

limited to any collision, grounding, fire, explosion, structural failure,

flooding or cargo shifting, or

(ii) any damage, failure or breakdown of the ship that

results in impairment of the safety of navigation, including but not limited

to, failure or breakdown of steering gear, propulsion plant, electrical

generating system, and essential shipborne

navigational aids,

(e) in relation to a large ship that

has on board a sewage treatment system, any damage, failure or breakdown of the

ship’s sewage treatment system that could result in the discharge of untreated

or inadequately treated sewage.

Division 2 Master’s obligations

87 Master must report reportable incident

(Article I (1) of Protocol I of MARPOL) (cf

former Act ss 10 (1) and 20 (1))

(1) The master of a ship must, without delay, report any

reportable incident that occurs in State waters in relation to the ship to the

Minister in the manner prescribed by the regulations.

Maximum penalty: $121,000.

(2) In a prosecution of a person for an offence against subsection

(1), it is a defence if the person proves that the

person was unable to comply with that subsection.

88 Master must provide supplementary report if Minister

requires it

(Article IV (b) of Protocol I of MARPOL) (cf

former Act ss 10 (6) and 20 (6))

The master of a ship must provide a supplementary report to the Minister

in relation to the reportable incident within the time prescribed by the

regulations and in accordance with the regulations if the Minister requests

such a report.

Maximum penalty: $121,000.

89 Master must provide supplementary report if further

developments arise

(Article IV (b) of Protocol I of MARPOL)

The master of the ship must provide a further supplementary report to

the Minister within the time prescribed by the regulations and in accordance

with the regulations if any significant further developments arise in relation

to the reportable incident after a report or supplementary report was required

under this Division.

Maximum penalty: $121,000.

International Dangerous Goods Code

Class 1: Explosives

Division 1.1: substances and articles which have a mass

explosion hazard

Division 1.2: substances and articles which have a

projection hazard but not a mass explosion hazard

Division 1.3: substances and articles which have a fire

hazard and either a minor blast hazard or a minor projection hazard or both,

but not a mass explosion hazard

Division 1.4: substances and articles which present no

significant hazard

Division 1.5: very insensitive substances which have a

mass explosion hazard

Division 1.6: extremely insensitive articles which do

not have a mass explosion hazard

Class 2: Gases

Class 2.1: flammable gases

Class 2.2: non-flammable, non-toxic gases

Class 2.3: toxic gases

Class 3: Flammable liquids

Class 4: Flammable solids;

substances liable to spontaneous combustion; substances which, in contact with

water, emit flammable gases

Class 4.1: flammable solids, self-reactive

substances and desensitized explosives

Class 4.2: substances liable to spontaneous

combustion

Class 4.3: substances which, in contact with

water, emit flammable gases

Class 5: Oxidizing substances

and organic peroxides

Class 5.1: oxidizing substances

Class 5.2: organic peroxides

Class 6: Toxic and infectious

substances

Class 6.1: toxic substances

Class 6.2: infectious substances

Class 7: Radioactive material

Class 8: Corrosive substances

Class 9: Miscellaneous dangerous

substances and articles

The numerical order of the classes and divisions is not that of the

degree of danger.

Marine Pollutants And Wastes

Many of the substances assigned to classes 1 to 9 are deemed as being

marine pollutants. Certain marine pollutants have an extreme pollution

potential and are identified as severe marine pollutants.

Wastes should be transported under the provisions of the appropriate

class, considering their hazards and the criteria in the Code. Wastes not

otherwise subject to the Code but covered under the Basel Convention* may be

transported under class 9. Alternatively, the classification may be in

accordance with other provisions.

*

For packing purposes, substances of all classes, other than classes 1,

2, 5.2, 6.2 and 7 and the self-reactive substances of class 4.1,

are assigned to three packing groups in accordance with the degree of danger

presented by the substance. The packing groups have the following meanings:

Packing group I: Substances presenting high danger;

Packing group II: Substances presenting medium danger; and

Packing group III: Substances presenting low danger.

The packing group to which a substance is assigned is indicated in the

Dangerous Goods List.

Dangerous goods are determined to present one or more of the dangers

represented by classes 1 to 9, marine pollutants and, if applicable, the degree

of danger (packing group) on the basis of the provisions.

Dangerous goods presenting a danger of a single class or division are

assigned to that class or division and the packing group, if applicable,

determined. When an article or substance is specifically listed by name in the

Dangerous Goods List, its class or division, its subsidiary risk(s) and, when

applicable, its packing group are taken from this list.

Dangerous goods meeting the defining criteria of more than one hazard

class or division and which are not listed by name in the Dangerous Goods List

are assigned to a class or division and subsidiary risk(s) on the basis of the

precedence of hazard provisions prescribed.

Marine pollutants and severe marine pollutants are noted in the

Dangerous Goods List and identified in the Index.

Dangerous Goods

shipped by sea must be described by their trade name and technical name

A vessel carrying

dangerous goods must have on board a Dangerous Cargo Manifest.

Form MO-4111

COMMONWEALTH OF

Marine Orders, Part 41

(Cargo and Cargo Handling - Dangerous Goods)

NOTICE OF INTENTION TO SHIP DANGEROUS GOODS

|

Shipper (Name and address) |

|

Container No……………………………………….. |

||||||

|

|

|

*

To…………………………………………………. (Prescribed person) |

||||||

|

|

|

Port

of ………………………………………………. |

||||||

|

Ship |

Port

of loading |

Date

of shipment |

||||||

|

Berth |

Port

of discharge |

Final

destination |

||||||

|

Marks

and numbers |

Number,

kind and size of packages |

Quantity

and description of goods including correct technical name (proper shipping

name), UN Number, class and flashpoint (if any) |

Gross

mass |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

* Marine Orders, Part 41 (Cargo and Cargo Handling - Dangerous Goods) provides: |

|

|||||||

|

‘5.4 - Prescribed person For the purposes of section 255 of the Navigation

Act and 5.1, the prescribed person is: |

I

CERTIFY THAT THE DANGEROUS GOODS TO WHICH THIS NOTICE RELATES HAVE BEEN

PACKED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE DETERMINATIONS UNDER 4.1 OF MARINE ORDERS, PART

41 (CARGO AND CARGO HANDLING - DANGEROUS GOODS) APPLICABLE TO THEM AND ARE IN

A PROPER CONDITION FOR CARRIAGE. …………………………………….. Shipper At……………..Date………………. |

|||||||

|

(a) |

if

it is intended to ship the goods at the port of Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane,

Port Adelaide or Fremantle, the person for the time being performing the

duties of the office of Assistant Director in the Regional Office of the

Department for the region in which the port is situated; |

|||||||

|

(b) |

if

it is intended to ship the goods at the port of Hobart the person for the

time being performing the duties of Assistant Director (Tasmania) in the

Regional Office of the Department; |

|||||||

|

(c) |

if

it is intended to ship the goods at a port in the State of Tasmania other

than the port of Hobart, the Departmental representative at the port, or the

person referred to in 5.4 (b); or |

|||||||

|

(d) |

if

it is intended to ship the goods at a port in a State or Territory other than

a port referred to in 5.4 (a), (b) or (c), the Departmental representative at

the port, or the person for the time being performing the duties of the

office of Assistant Director in the Regional Office of the Department for the

region in which the port is situated.’ |

|||||||

Appendix C

Case Studies- Oil Spills

Major Oil Spills in

A brief summary on each spill

is provided below.

|

Date |

Vessel |

Location |

Oil amount |

|

|

Korean Star |

|

600 tonnes |

|

|

Al Qurain |

|

184 tonnes |

|

|

Arthur Phillip |

|

unknown |

|

|

Sanko Harvest |

|

700 tonnes |

|

|

Kirki |

WA |

17,280 tonnes |

|

|

Era |

Port Bonython SA |

300 tonnes |

|

|

Iron Baron |

Hebe Reef TAS |

325 tonnes |

|

|

Mobil Refinery |

Port Stanvac SA |

230 tonnes |

|

|

Laura D’Amato |

|

250 tonnes |

Brief information on spills

Korean

Star -

A major incident in

Al

Qurain -

On

Arthur

Phillip -

On

Investigations into the source of the spill were initiated and the

Australian registered oil tanker Arthur Phillip was found to be responsible for

the spill. The owners and the master were prosecuted and fined.

Sanko

Harvest -

The Sanko Harvest struck a reef off

Kirki -

On

Era -

On

Iron

Baron -

The 37 500 dwt BHP-chartered bulk carrier Iron Baron grounded on Hebe

Reef in the approaches to the

Mobil

Refinery -

On the morning

Laura

D’Amato -

On the evening of